After working for the last three years with TFS’s classic source control TFVC, I recently moved to a new company and with that, to Git.

Before working with Git, I loved working with TFVC. I thought it was great and pretty much the most I can expect from a source control.

Git, however, changed the way I work with source control and even the way I think about source control.

This post is a small taste of what Git does and how my workflow changed accordingly. It is not a Git tutorial, but rather my impressions from it. I do link at the end to some additional resources.

Git is HARD to start with

Git has a pretty steep learning curve. Crazy steep when comparing to TFVC (Original TFS) or Subversion (SVN).

Things are not intuitive in Git when starting. At least they weren’t for me after working for so long with TFVC and SVN. And the reason is that there is a core difference between them.

To work with Git, we have to understand how Git thinks. And at the core, we have to understand DVCS.

DVCS vs CVCS

Git is a Distributed Version Control System – DVCS. Whereas TFVC is Centralized Version Control System – CVCS.

DVCS means each developer has the entire repository, including the entire change history on his/her local machine. So the developer can see changeset history offline or commit (check-in) changes offline to his local repository.

In CVCS, the developer has a copy of the repository file system on his machine. So offline actions like commits (check-ins) and seeing history are impossible since the local repository can’t save “changes”.

So what are the implications of this?

Git vs TFVC… Blue pill please. #Git #TFVC #TFS #CVCS #DVCS pic.twitter.com/NcyzCOd1U5

— Donovan Brown (@DonovanBrown) 5 February 2015

In Git, everything is done locally

Since the entire repository is local, we do everything locally. This includes, but not limited to:

- Committing changes (Check-in)

- Viewing commit history

- Creating a new branch

- Merging branches

- Moving to a different branch

- Deleting branches

- Reverting older commits

Of course, at some point, we have to sync our changes to the remote repository (“Push”).

“Check-in” in Git is divided into 2 parts: Commit and Push.

This is actually a big deal. It allows a much better workflow for us developers. I can now commit locally whatever I want – Ugly code, comments, and work in progress. The other developers won’t get those changes. And when my code is nice and clean, I can Push all my commits to the remote repository.

Another concept in Git is Staging. This is a bit like Included / Excluded changes in TFS. Only staged files will be committed. Which is convenient since I usually have modified configuration files that I don’t want to be committed.

Git is fast, really fast!

Committing (Which is like check-in to the local repository) takes less than a second on my PC. Blame (Annotate) , viewing history or filtering by commits is incredibly fast. This is partly because in Git everything is done locally. But also, because of Git’s unique way to save the repository. Git works with snapshots instead of with changes .

Branches and Merges are really where the power of Git over TFVC shines.

Branches in Git

In TFVC, Branch will create a new directory with a copy of all files and directories of the parent Branch. For a developer to work on that new branch, he will have to copy that directory to his hard disk, essentially having another folder with the source code.

In Git, each branch is not a copy of the files from the parent branch. Instead, it’s simply a pointer to the Commit in the parent Branch from where we created our new branch.

So when we want to work on a different branch, we tell Git “Move to another branch” (Checkout command) and Git will change our working area to match the desired branch. This is very fast since it’s done locally. Git already contains all the branches on the local machine.

Merging is a lightweight operation. We can merge any branch to any branch. We can merge the entire difference or a specific Commit. Git will find the “Base” Commit where the branches split and allow us to resolve conflicts (This is the same as in TFS)

A good practice with Git is to create a new branch to work on a big feature. Eventually, merging that branch to the master branch and discarding the new branch entirely.

Here’s a good tutorial on branches in Git.

Tooling and Git command line

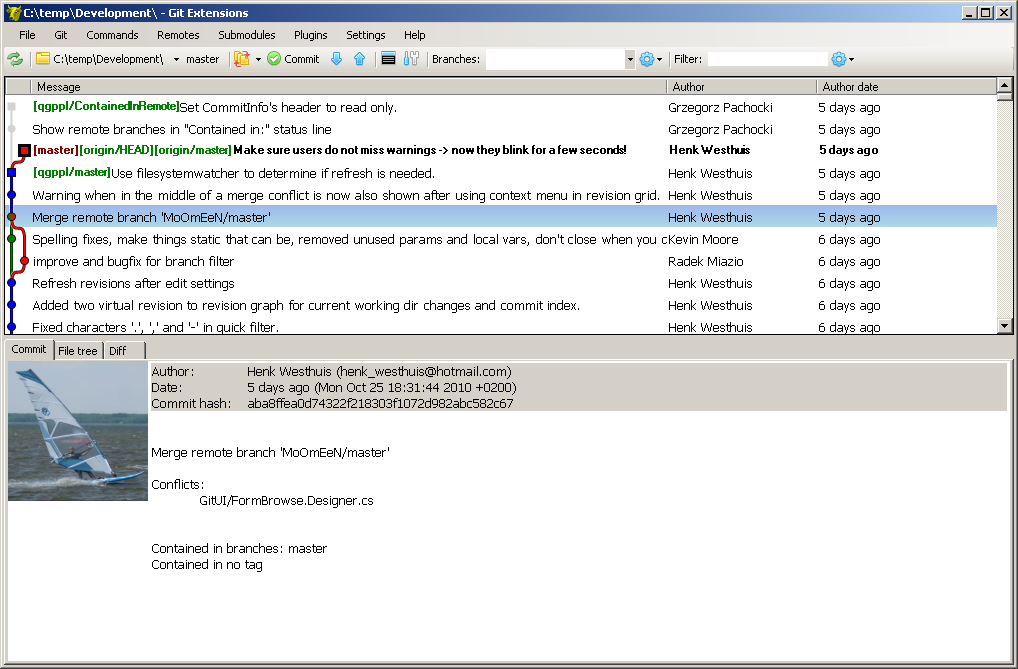

Git is a command line based tool. You can do everything with the command line, and I know there are a lot of Git users that advocate that. However, nowadays there are some excellent tools that provide a nice GUI to work with Git. One such tool is Git Extensions .

Also, there’s integration with Git in Visual Studio, but I find Git Extensions to be more convenient.

Git Extensions actually gives you a Console window where you can use Git command line with several Linux commands like Grep. This is very useful. Especially when seeing answers in StackOverflow, I can just copy-paste them to my console window.

I don’t see why anyone would choose to use Git with the command line when there are such great free tools like Git Extensions.

But then again, be careful taking advice from the internet 🙂

My transition to Git

Once I got over the initial Git shock, my working flow became faster. There are a number of reasons for that. First of all, Git itself is really fast. Second, with Git I do local commits which saves me time. I can commit my work in progress code without worrying it’s buggy and will disrupt another developer’s work. So I don’t have to save my pending changes for a long time until I’m sure whatever I’m doing is good enough.

This is one of those things that I never realized I needed until I started working this way.

The third reason Git made my life better is branches. Creating merges and working on a side branch become a part of my workflow.

Summary

I am definitely falling in love with Git.

Full disclosure: I also fell in love with TFVC and TFS when I started working with those.

Git is faster and more powerful than TFVC or SVN. It rapidly becomes the world standard to source control system.

Git is also pretty hard and I’m sure many a developer spent a lot of hours trying to decipher why Git does what it does. TFVC is definitely easier to start with and more intuitive.

I don’t think moving to Git is necessarily the right choice for everyone.

Here’s my very opinionated advice about organizations considering moving to Git:

- When starting a new project with no developers yet, use Git.

- If you have a small team with at least one strong developer experienced with Git, move to Git.

- If you have a big team working with TFVC and not enough people experienced with Git, moving to Git will be costly. But maybe it will pay in the long run.

- In the end, it’s all about the quality of people. Git is more powerful but harder. If you have superstar developers on your team, they will figure it out. Move to Git.

Read about GitFlow and SourceTree Git-Client (which implements GitFlow as a feature)

Very cool, I liked it! Gives a nice structure for everything.

I can follow that branch model without using the Git flow commands though... Git has too many commands as is :)

Sweet, sounds much more robust and less prone to people getting in each other's way, as well as a faster way to getting to know the nooks and crannies ('s how it sounds like, xD).

Very true. With just one small price - A steeper learning curve and more room to make mistakes

"Once I got over the initial Git shock, my working flow became faster." --- But I am willing to bet it also became more isolated (there is much more to the "distributed vs. centralized" than where the repository lives.

Now there are times when isolation is good. The perfect example is different vendors each producing their own version of Linux.

But in a highly integrated team, there are many things that are centralized, and the isolation caused by Git* is likely to have a negative impact on all of them.

david(dot)corbin(at)dynconcepts(dot)com for further information.

David, I see your point and agree that with Git's branches and local commits, it's very easy to work SOLO without conflicts from other developers. Whereas a centralized source control sort of makes you sync with everyone else as soon as possible. I see this as an advantage to Git since you have the flexibility to choose how often you'll merge to the main development branch.

For me personally, I try to merge back as often as I can. So I will create a branch for a new feature, but will make sure to do back-merges (or rebases) from the main branch to my feature branch every couple of days to have my code as close as possible to the other team.

Having been a long-time TFS user I'm now having a go with Git but am struggling to understand the concept of local branches: If I create a local branch from "master", make a change to the solution in that new branch, then switch back to "master", I still see the pending changes. I think I was expecting the solution to "refresh" in some way, and show me the solution as it exists in the master branch.

If I commit the change on the new branch before switching back to master then I do see the behaviour I was expecting, but I don't really understand why. Switching between local branches with uncommitted changes feels like a disaster waiting to happen, and tbh I'm struggling to think of a use for them?!

Hi Andrew,

The local changes are really not part of any branch until you commit them. In fact, if you try to change branches when your local change somehow conflicts with the target branch, git won't let you do that.

It really one of those things that you need to get used to. Eventually, it becomes quite useful. For example, you might have configuration changes to development environment as part of your uncommitted changes.

This confused me to no end in the beginning. Essentially, changes are not associated with any branch until you say so. I can make changes in one branch but then go to another branch and they are still there. Huh??? But once I commit a set of changes to a branch then they are permanently associated with that branch. Ironically enough, this actually saved me a couple times when I made changes and realized I was on the wrong branch. I hadn't committed the changes yet so I switched to the proper branch and made the commit safely. Disaster averted.

Yup. This probably happened to most users when getting started

Git should not allow you to switch to branch B if you have made changes to a file in branch A. The only exception to this is if it's a newly created file that is not in source control yet. If I want to switch branches, I have to stash my changes first. You are correct that it is a disaster waiting to happen because it totally defeats the purpose of branches.

Great article (and comment replies) - after seeing others go through the same pains it's given me more of an impetus to switch. A couple more questions:

If I make changes to a file then do a "compare" in VS, am I right in saying that it compares it against the local repo version? If so, is there any way to compare it against the remote repo version?

Lastly, what happens if I have uncommitted changes when I do a pull? Will those files remain unchanged, or will the remote repo changes get merged into them? I'm guessing they'll remain unchanged, as I'm assuming uncommitted changes reside in some kind of working directory (akin to a TFS workspace) separate from the local repo (and a merge will only take place when committing).

git pullis shorthand forgit fetch && git merge. So the remote changes will get merged in just as with any other merge—and just as with any other merge, Git will alert you to conflicts it can't resolve.I have used TFVC and Git. I am probably more experienced with TFVC than with Git. My biggest problem with Git is the intuitiveness of it. It requires too much thinking to make sure I don't screw something up. I just want to check my files in and be done without having to think through all of the steps required with doing the same in Git. I am always worried about the error-prone nature of Git if someone doesn't know what they are doing.

One other problem with Git is the lack of exclusive locks. We have some files in our source project that are very difficult to merge because they are created using a code generator (IBM Rhapsody). Thus, when someone is making a change to these specific files, we don't want others changing them until the person with the lock is done. TFVC accommodates this requirement, whereas Git does not.

Also, TFVC provides Shelvesets to temporarily check-in files that are not placed on the main TFVC repository, which is similar to Git local version control (albeit not as quick to accomplish).

I understand that Git is much more feature-rich than TFVC, but I prefer the simplicity of TFVC.

I hear you Ken. For me, the intuitiveness of Git was kind of solved for me when I started using GitExtensions. It's now as intuitive as TFVC. The lock thing is a problem indeed. Don't know how you would solve that one... And the shelvesets can be converted to branches. It's not as intuitive, but a branch can be used just as a shelveset. When you need to "unshelve", just merge that branch into your current branch.

Git is extremely intuitive once you understand its fundamental operations, which are rather different from those of CVCSs. Basically, it creates a DAG of commit objects, each of which has a unique ID and a pointer to its parent, and synchronizes DAGs between repositories (which is what push and pull do). Once you absorb that mental model, everything becomes extremely predictable and easy to understand.

As for your locking issue, here's how I'd approach it. In general, generated code doesn't belong in the source repository; it should be generated as part of the build process from files that are in the source repository. If for some reason that's not possible, Git allows use of custom merge drivers for particular types of files, so you should be able to define the strategy you need and get rid of the locks. (I've never needed locks in 20 years of software development, FWIW.)

Git Merge Work Better than TFS Merge.

https://www.richard-banks.o...