Event registrations in C# (and .NET in general) are the most common cause of memory leaks. At least from my experience. In fact, I saw so much memory leaks from events that seeing += in code immediately makes me suspicious.

While events are great, they are also dangerous. Causing a memory leak is very easy with events if you don’t know what to look for. In this post, I’ll explain the root cause of this problem and give several best practice techniques to deal with it. In the end, I’ll show you an easy trick to find out if you indeed have a memory leak.

Understanding Memory Leaks

In a garbage collected environment, the term memory leaks is a bit

The answer is that with a garbage collector(GC) present, a memory

Let’s see an example:

public class WiFiManager

{

public event EventHandler <WifiEventArgs> WiFiSignalChanged;

// ...

}

public class MyClass

{

public MyClass(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged += OnWiFiChanged;

}

private void OnWiFiChanged(object sender, WifiEventArgs e)

{

// do something

}

public void SomeOperation(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

var myClass = new MyClass(wiFiManager);

myClass.DoSomething();

//... myClass is not used again

}

In this example, let’s assume WiFiManager is alive throughout the lifetime of the program. After executing SomeOperation, an instance of MyClass is created and never used again. The programmer might think the GC will collect it, but not so. The WiFiManager holds a reference to MyClass in its event WiFiSignalChanged and it causes a memory leak. The GC will never collect MyClass.

1. Make sure to Unsubscribe

The obvious solution (although not always the easiest) is to remember to unregister your event handler from the event. One way to do it is to implement IDisposable:

public class MyClass : IDisposable

{

private readonly WiFiManager _wiFiManager;

public MyClass(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

_wiFiManager = wiFiManager;

_wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged += OnWiFiChanged;

}

public void Dispose()

{

_wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged -= OnWiFiChanged;

}

private void OnWiFiChanged(object sender, WifiEventArgs e)

{

// do something

}

Of course, you’d have to make sure to call Dispose. If you have a WPF Control, an easy solution is to unsubscribe in the Unloaded event.

public partial class MyUserControl : UserControl

{

public MyUserControl(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

InitializeComponent();

this.Loaded += (sender, args) => wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged += OnWiFiChanged;

this.Unloaded += (sender, args) => wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged -= OnWiFiChanged;

}

private void OnWiFiChanged(object sender, WifiEventArgs e)

{

// do something

}

}

Pros: Simple, Readable code.

Cons: You can easily forget to unsubscribe, or won’t unsubscribe in all cases which will lead to memory leaks.

NOTE: Not all event registrations cause memory leaks. When registering to an event that you will outlive, there will be no memory leak. For example, in a WPF UserControl you might register to a Button’s Click event. This is fine and there’s no need to unregister since the User Control is the only one referencing that Button. When there’s no-one referencing the User Control, there will be no-one referencing the Button as well and the GC will collect both.

2. Have handlers that unsubscribe themselves

In some cases, you may want to have your event handler to occur just once. In that case, you’ll want the code to unsubscribe himself. When your event handler is a named method, it’s easy enough:

public class MyClass

{

private readonly WiFiManager _wiFiManager;

public MyClass(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

_wiFiManager = wiFiManager;

_wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged += OnWiFiChanged;

}

private void OnWiFiChanged(object sender, WifiEventArgs e)

{

// do something

_wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged -= OnWiFiChanged;

}

}

However, sometimes you’d want your event handler to be a lambda expression. In that case, here’s a useful technique to have it unsubscribe itself:

public class MyClass

{

public MyClass(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

var someObject = GetSomeObject();

EventHandler<WifiEventArgs> handler = null;

handler = (sender, args) =>

{

Console.WriteLine(someObject);

wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged -= handler;

};

wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged += handler;

}

}

In the above example, the lambda expression is useful because you can capture the local variable someObject, which you wouldn’t be able to do with a handler method.

Pros: Simple, readable, no chance for memory leaks as long as you’re sure the event will fire at least once.

Cons: Usable only in special cases where you need to handle the event once.

3. Use Weak Events with Event Aggregator

When you reference an object in .NET, you basically tell the GC that object is in use, so don’t collect it. There’s a way to reference an object without actually saying “I’m using it”. This kind of reference is called a Weak Reference. You’re saying instead “I don’t need it, but if it’s still there then I’ll use it”. In

We can use that in several ways to prevent memory leaks. One popular design pattern is to use an Event Aggregator

. The concept is that anyone can subscribe to events of type T, and anyone can also publish events of type T. So when a class publishes the event, all subscribed event handlers will be invoked. The event aggregator references everything using WeakReference. So even if an object

Here’s an example using Prism’s popular event aggregator (available with the NuGet Prism.Core )

public class WiFiManager

{

private readonly IEventAggregator _eventAggregator;

public WiFiManager(IEventAggregator eventAggregator)

{

_eventAggregator = eventAggregator;

}

public void PublishEvent()

{

_eventAggregator.GetEvent<WiFiEvent>().Publish(new WifiEventArgs());

}

public class MyClass

{

public MyClass(IEventAggregator eventAggregator)

{

eventAggregator.GetEvent<WiFiEvent>().Subscribe(OnWiFiChanged);

}

private void OnWiFiChanged(WifiEventArgs args)

{

// do something

}

public class WiFiEvent : PubSubEvent<WifiEventArgs>

{

// ...

}

Pros: Prevents memory leaks, relatively easy to use.

Cons: Acts as a global container for all events. Anyone can subscribe to anyone else. This makes the system hard to understand when overused. No separation of concerns.

4. Use Weak Event Handler with regular events

With some code acrobatics, it’s possible to utilize Weak Reference with regular events. This can be achieved in several different ways. Here’s an example using Paul Stovell’s WeakEventHandler :

public class MyClass

{

public MyClass(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

wiFiManager.WiFiSignalChanged += new WeakEventHandler<WifiEventArgs>(OnWiFiChanged).Handler;

}

private void OnWiFiChanged(object sender, WifiEventArgs e)

{

// do something

}

}

public class WiFiManager

{

public event EventHandler<WifiEventArgs> WiFiSignalChanged;

// ...

public void SomeOperation(WiFiManager wiFiManager)

{

var myClass = new MyClass(wiFiManager);

myClass.DoSomething();

//... myClass is not used again

}

I really like this approach because the publisher, WiFiManager in our case, is kept with standard C# events. This is just one implementation of this pattern, but there are actually many ways you can go about it. Daniel Grunwald wrote an extensive article about the different implementations and their differences.

Pros: Utilizes standard events. Simple. No memory leaks. Separation of concerns (unlike Event Aggregator).

Cons: The different implementations of this pattern have subtleties and different problems. The implementation in the example actually creates a wrapper object registered that is never collected by the GC. Other implmentations can solve this, but have other issues like additional boilerplate code. See more information on this in Daniel’s article .

Problems with the WeakReference solutions

Using WeakReference means the GC will be able to collect the subscribing class when possible. However, the GC doesn’t collect unreferenced objects immediately. It does randomly as far as the developer is concerned. So with weak events, you might have event handlers invoked in objects that shouldn’t exist at that point.

The event handler might do something harmless like update inner state. Or it might change the program state until some random time the GC decides to collect it. This type of behavior is indeed dangerous. Additional reading on this in The Weak Event Pattern is Dangerous .

5. Detecting memory leaks without a memory profiler

This technique is to test for existing memory leaks, rather than coding patterns to avoid them in the first place.

Suppose you suspect a certain class has a memory leak. If you have a scenario where you create one instance and then expect the GC to collect it, you can easily find out if your instances will be collected or if you have a memory leak. Follow these steps:

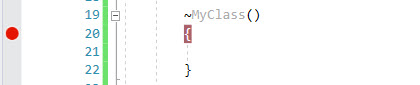

1.Add a Finalizer to your suspect class and place a breakpoint inside:

- Add these magic 3 lines to be called in the start of the scenario:

GC.Collect();

GC.WaitForPendingFinalizers();

GC.Collect();

This will force the GC to collect all unreferenced instances (don’t use in production) up to now, so they won’t interfere with our debugging.

-

Add the same 3 magic lines of code to run after the scenario. Remember, the scenario is the one where your suspect object is created and should be collected.

-

Run the scenario in question.

In step 1, I told you to place a breakpoint in the class’s Finalizer. You should actually pay attention to that breakpoint after the first garbage collection’s finished. Otherwise you might be confused with older instances being disposed. The important moment to notice is whether the debugger stopped in the Finalizer after your scenario.

It helps to also place a breakpoint in the class’s constructor. This way you can count how many times it was created versus how many times it was finalized. If the breakpoint in the finalizer was triggered, then the GC collected your instance and everything’s fine. If it didn’t, then you have a memory leak.

Here’s me debugging a scenario that uses WeakEventHandler from the last technique and doesn’t have a memory leak:

Here’s another scenario where I use regular event registration and it does have a memory leak:

Summary

It always amazes me how C# might seem like an easy language to learn, with an environment that provides training wheels. but in reality, it’s far from it. A simple thing like using events can easily turn your application to a bundle of memory leaks by an untrained hand.

As far as the correct pattern to use in code, I think the conclusion from this article should be that there is no right and wrong answer for all scenarios. All provided techniques, and the variations of

This turned out to be a relatively big post, and yet I stayed at a relatively high level with this issue. This just proves how much depth exists in these matters and how software development never ceases to be interesting.

For more information on memory leaks, check out my article Find, Fix, and Avoid Memory Leaks in C# .NET: 8 Best Practices . It’s got tons of information from my own experience and other senior .NET developers that advised me for it. It includes info on Memory Profilers, Memory leaks from unmanaged code, monitoring memory and more.

I’d love you to leave some feedback in the comments section. And be sure to subscribe to the blog and be notified of new posts.